This article is a collaboration between �������� and:

ROME -- Should the SPRINT trial be used by guideline committees to lower systolic blood pressure targets? After listening to a high-powered debate at the European Society of Cardiology meeting in Rome on Sunday, most audience members gave thumbs down to the proposal.

The audience appeared to be swayed by a strong argument from (Oslo), who said the trial was difficult to interpret at best and, in at least one important respect, unethical.

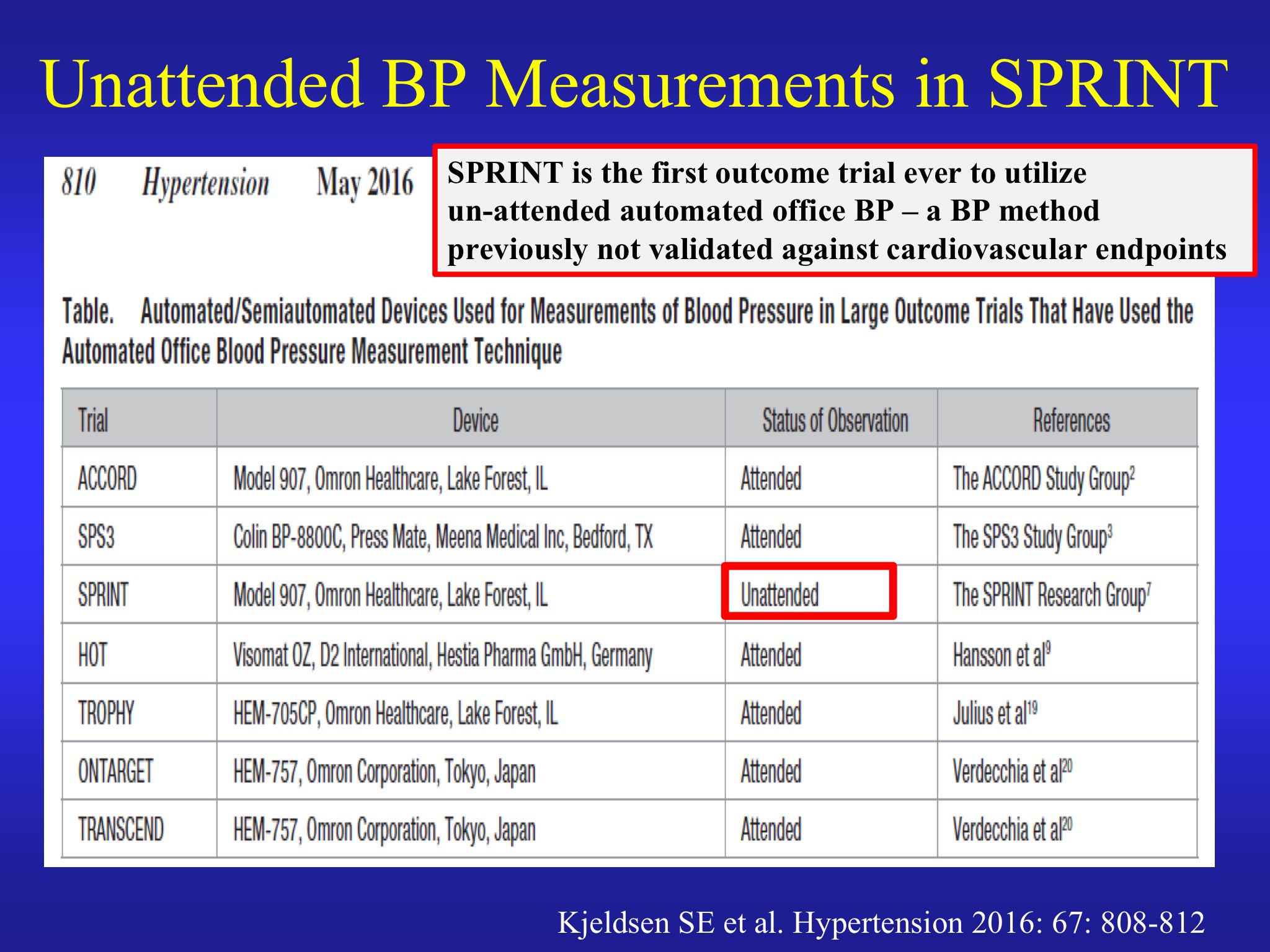

Kjeldsen's strongest point was that the trial adopted an unprecedented and novel method to measure blood pressure, making it impossible to compare with previous trials. In all the major recent hypertension trials, blood pressure had been measured three separate times with an automatic monitor in the presence of a healthcare professional.

In SPRINT, however, the healthcare professionals were trained to leave the room before the measurements started. This method has not been validated and Kjeldsen presented multiple lines of evidence suggesting that it would lead to much lower blood pressure readings, as much as 10 to 20 mm Hg lower than usual. He said that the systolic BP target of 120 mm Hg in SPRINT when examined in this light is actually closer to the prevailing standard of 140 mm Hg in other trials.

He was also strongly critical of the SPRINT investigators for not reporting this significant fact in or in its . The paper simply said: "Dose adjustment was based on a mean of three blood-pressure measurements at an office visit while the patient was seated and after 5 minutes of quiet rest; the measurements were made with the use of an automated measurement system (Model 907, Omron Healthcare)."

Kjeldsen said it was unethical not to report the unattended nature of the measurements, since many clinicians have tried to apply the findings to their patients but were not aware of this important change.

He also noted that nearly 500 people out of the 9,361 enrolled discontinued treatment during the trial and more than 250 were lost to followup, further limiting interpretation of the trial.

One of the striking findings of SPRINT was the reduction in heart failure in the intensive treatment arm. But, said Kjeldsen, given participants' age and other risk factors the SPRINT population had a very high risk of heart failure. He said that differences in the main outcomes may have been due to greater and more effective use of diuretics in the treatment group than in the control group. "Thus, the main finding is likely an artifact caused by increased risk of heart failure in the standard treatment group because of less diuretic treatment."

Further, the intensified diuretic regimen in the aggressive treatment group also likely led to a significant increase in adverse events, including hypotension, syncope, electrolyte imbalance, and acute kidney injury or acute renal failure. Kjeldsen cited the that calculated that for every 1,000 persons treated for 3.2 years with the more aggressive target "an average of 16 persons will benefit, 22 persons will be seriously harmed, and 962 will not experience benefits or harms."

"SPRINT should have no implications for guidelines or clinical practice," he concluded.

Kjeldsen also raised the ethical issue -- which I wrote about -- concerning the early and potentially misleading release of the results 2 months before the publication of the trial in NEJM. "In the view of this reviewer, it appears unethical that a closed and limited group of SPRINT investigators under the leadership of the NIH Director makes a press release 2 months prior to study publication," he said.

(Memphis, Tenn.) a SPRINT investigator, was charged with defending the proposition that SPRINT should be used by guideline committees to lower blood pressure targets. Cushman chose a less aggressive position, explaining the trial and defending it from some of the criticisms launched by Kjeldsen. The main substance of his talk was a detailed presentation of the main findings of SPRINT.

He took issue with the charge that there were more serious adverse events (SAEs) in the intensive treatment group. Overall there was no significant difference in these events. Moreover, he said, it is often possible to successfully manage SAEs, making these of lesser concern than a mortality event which, obviously, can not be managed.

Cushman also addressed the idea that decreased use of diuretics may have explained the higher rate of heart failure in the control group. In fact, he said, patients in the control group had more diuretic use after they came in the study, but he acknowledged that it may have been possible that some patients were removed from some therapies during the study as part of their treatment strategy.

He suggested that the optimal target may lay within the range of 120 to 135 mm Hg. He also pointed out that, in practice, a lower target would lead to more people reaching a higher target. (London), a conference program chair, ended the session by emphasizing that, even now, more than half of hypertensive patients don't reach the current goal of 140 mm Hg.

Earlier, setting the stage for the debate, (Milan), raised questions about the trial and its interpretation, perhaps putting Cushman at a disadvantage. Mancia said that the SPRINT evidence was limited to high-risk patients and might not apply to younger or lower-risk populations. He also said that it is possible that optimal targets may vary for each individual, and may even vary at different times for individual patients) and said that this may "limit the practical value of trial information."

Mancia also said that the question about unattended BP measurement was "quite disturbing," but argued that the difference between observed and unobserved blood pressure in high-quality research is much smaller, more like 5 mm Hg than 15 mm Hg. "The unattended measurement makes it very difficult to make comparisons with other trials," he said.

Update:

(Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles), offered the following comment in response to the SPRINT debate:

“I have given two invited lectures at AHA meetings talking about consumer report guide to interpretation of trials. I use a scale from 1 to 5 stars (5 being the highest) based on the quality and quantity of evidence. Even though the effect size of the primary endpoint was large (25% RRR) and statistically persuasive (P=0.004), the quality was moderate (open-label study, prematurely stopped with 5.5% missing data and no exploration of missing data on the PEP), thereby earning a 3-star rating. In my book, only 4 or 5 star-rated trials are practice changing!

The fact that stroke, which is very sensitive to BP reduction, was not favorably impacted, but HF and death was, raises additional questions! In my book, ‘quality’ trumps ‘quantity’!”

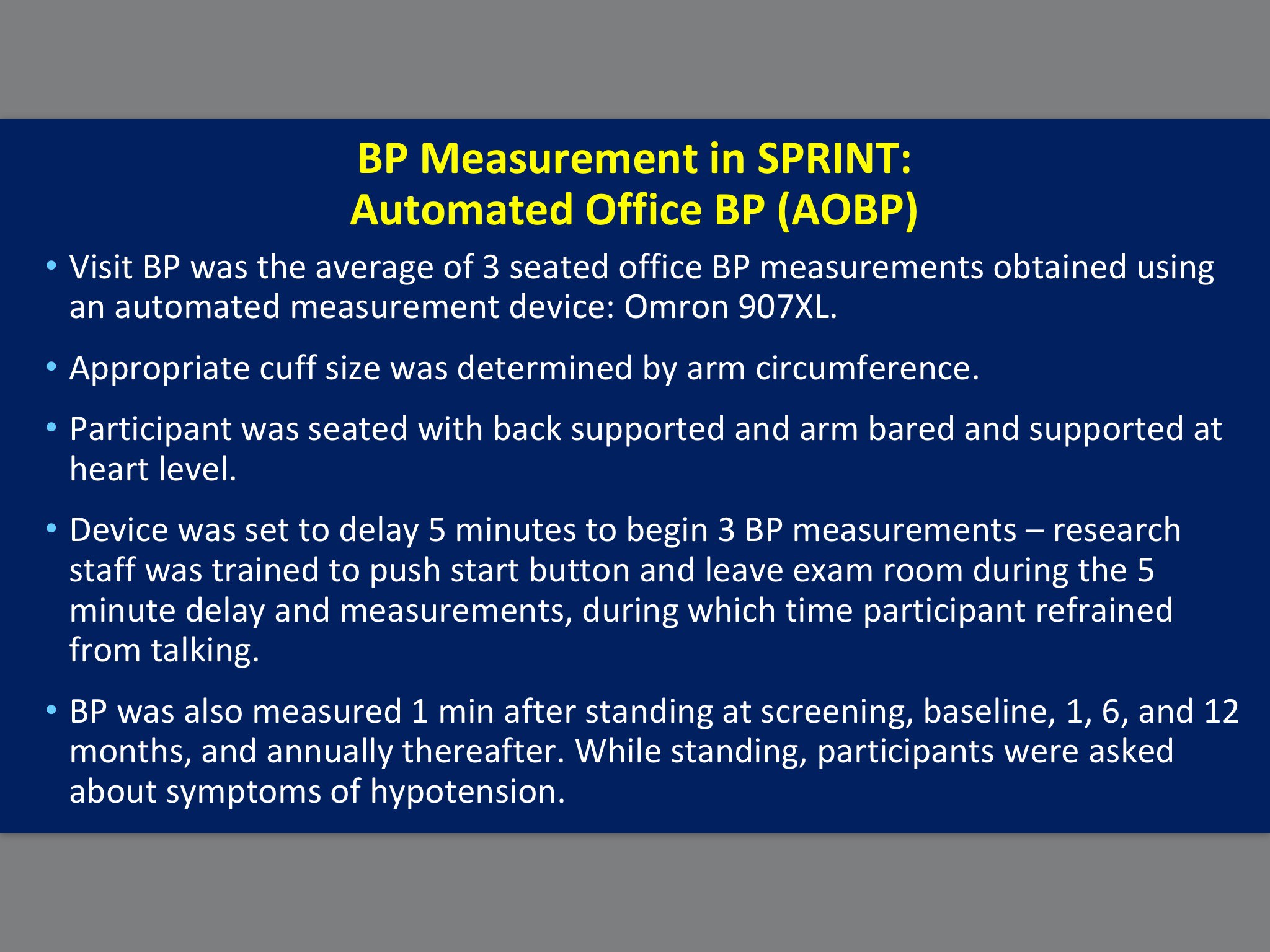

I have been informed that there are yet further questions about the precise details of blood pressure monitoring in SPRINT. According to one source close to the trial, both Cushman on behalf of SPRINT and Kjeldsen in opposition were wrong about details of blood pressure measurement despite both agreeing on them during the debate. The slides for each are presented below. It should also be noted that Kjeldsen’s larger point remains uncontested, which is that blood pressure measurement in SPRINT was not performed in the same way as previous trials, thereby making it difficult to compare the SPRINT results with those trials. I will update this post as more information becomes available.

Here is Cushman’s slide:

And here is Kjeldsen’s slide: